Medicaid prescriptions for opioid use disorder are on the rise. Here's what you need to know

This story originally appeared on Ophelia and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Medicaid prescriptions for opioid use disorder are on the rise. Here's what you need to know

Opioid use disorder, or OUD, has grown into a nationwide epidemic, and state Medicaid programs play an integral role in mitigating it.

The CDC classifies opioids into three categories, the first being prescription opioids, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, and methadone, which treat moderate to severe pain. The second category, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, are much more potent than opioids in the prescription group and are typically assigned to mitigate late-stage cancer pain. The final category includes only a single illegal substance—heroin.

When people using opioids experience physical, legal, social, and interpersonal challenges resulting from recurrent substance use and abuse, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders defines them as meeting the criteria for OUD. Opioid addiction is characterized by increased tolerance, withdrawal syndrome, and a persistent yet unsuccessful desire to quit. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioid-related death rates jumped 38% from 2019 to 2020. About 3 in 4 lethal drug overdose cases in 2020 involved an opioid.

Even prescription opioids used within allowed amounts and appropriate time intervals may have adverse effects and lead to addiction. Patients often experience withdrawal symptoms, including muscle and bone pain, vomiting, diarrhea, sleep problems, and severe cravings.

The U.S. has seen three waves of the opioid overdose epidemic, according to the CDC, and some researchers also see evidence of a fourth wave ushered in by stimulants and the COVID-19 epidemic. It wasn't until the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid expansions in some states that prescriptions to treat OUD became more accessible.

Ophelia explored trends in Medicaid prescriptions for opioid use disorder using data from the Kaiser Family Foundation to learn more about how these medicines are changing the opioid epidemic in the U.S.

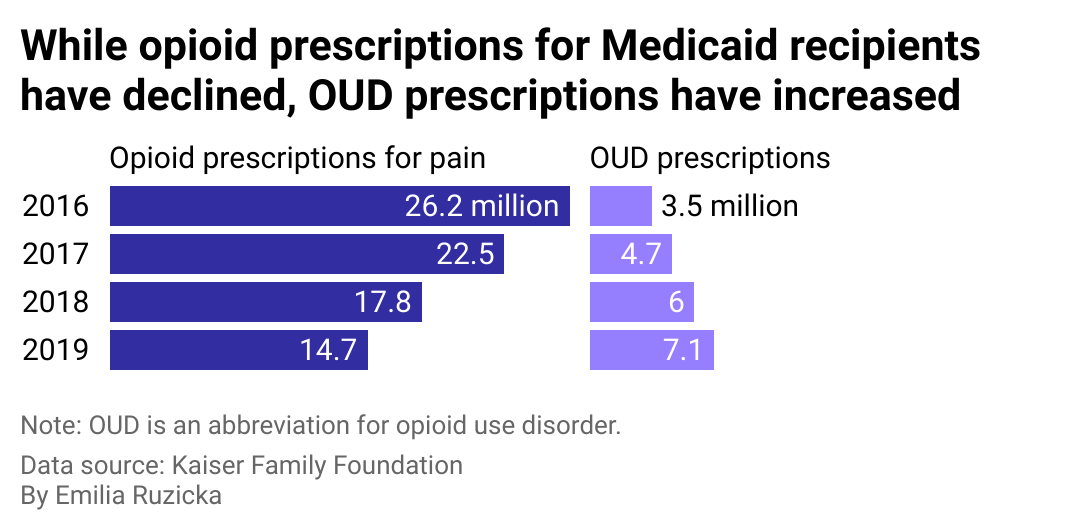

Trends in prescriptions for opioids and OUD

Prescriptions are both the catalyst of the opioid epidemic and part of the solution to it. Medication prescribed to people with opioid use disorder—buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone—help prevent relapse and reverse potentially fatal overdoses.

In 2016, pregnant women constituted the group of Medicaid enrollees with the highest share of opioid prescriptions, at about 24%. This figure dropped by more than 8 percentage points in just three years.

By 2019, people with disabilities accounted for the largest share of such prescriptions. Changing state policies have been the main driving force behind the overall downward trend of opioid prescriptions and the evolving composition of opioid-eligible Medicaid recipients.

All 50 states have introduced quantity limits, and many have reformed clinical criteria claim systems, launched step therapy, and instituted prior authorization requirements. Such efforts have decreased the accessibility of opioid prescriptions for pain treatment.

Conversely, OUD prescriptions became more accessible over the same period. Prescriptions for buprenorphine, a drug that treats OUD, nearly doubled from 2016 to 2019, as states worked to increase the availability of OUD prescriptions. New laws raised patient limits and expanded the list of medical professionals who could prescribe the drug.

Working to put opioids—and OUD medication—in the right hands

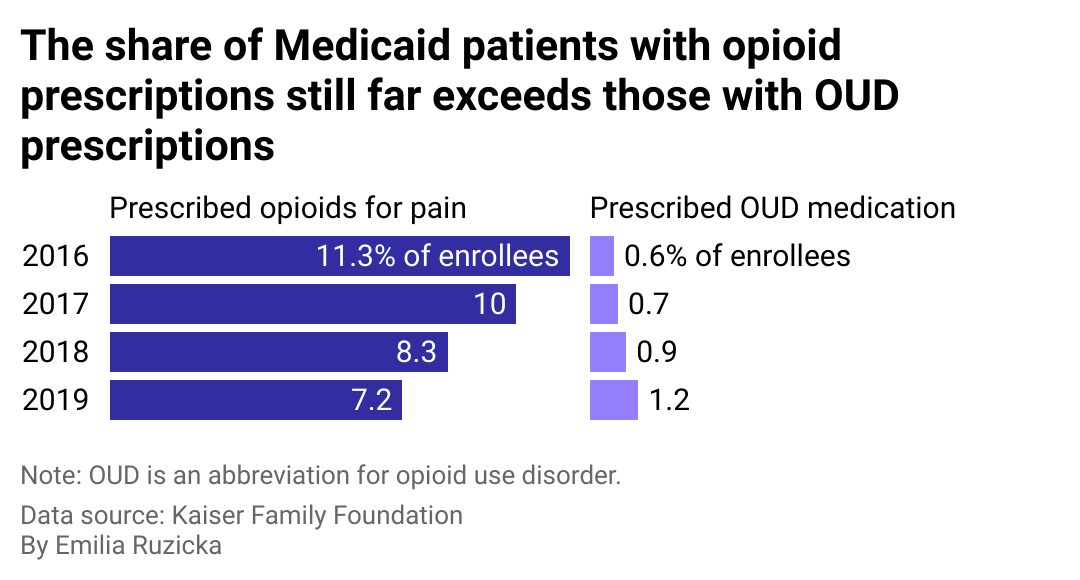

While OUD medications have documented positive effects on the health outcomes of opioid-dependent patients, various barriers preventing broader coverage persist. In 2019, fewer than 35% of adults suffering from OUD received necessary treatment. Among Medicaid patients, the number of prescription opioids to treat pain outpaces the number of prescriptions to treat OUD.

Fear of stigma is a significant factor suppressing the number of patients seeking OUD treatment. Nationwide, negative attitudes toward people with OUD prescriptions surpass those reported for those receiving medical treatment for mental illness disorders. Among health care providers, concerns about the possible diversion of OUD medication contribute to the reluctance of prescribers to treat individuals with OUD.

The Department of Health and Human Resources (HHS) defines diversion as "the illegal distribution or abuse of prescription drugs or their use for purposes not intended by the prescriber."

Diversion can occur nearly anywhere in a prescription drug's supply chain, from manufacture through distribution to pharmacies and even directly to the patient. In recent years, the illegal distribution of synthetics, notably fentanyl, has increased. A 2018 national survey of buprenorphine prescribers found that one-third of respondents perceived the risk of medication diversion as a significant concern, with about half saying they would be unwilling to see a patient suspected of diversion again.

To combat this issue, federal agencies such as HHS and the Drug Enforcement Agency and hospital and pharmacy networks have created guidelines, such as recommending that health care professionals use electronic prescriptions instead of paper, stick to strict refilling policies, and check for a full medication history from state prescription drug monitoring programs. They also recommend that doctors prescribe opioids only when alternative therapies have been attempted and refer patients with long-term chronic pain to specialized practices.

Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.